TEXT: Selina Ting

IMAGES: Courtesy of Tina Keng Gallery

Original Text published on COBO Social on 8 May 2018. Courtesy of COBO Social

“Je suis obligé de ne pas quitter Paris afin de vivre la vie de bohème,” (I must not quit Paris in order to live a bohemian life), wrote Sanyu (1901-1966) in a letter to his patron Johan Franco (1908-1988), the Dutch composer and descendant of the Van Gogh family in 1931. Precisely a decade after moving to Paris from his native city of Sichuan in China, this was the turning point of Sanyu’s life. Despite a declining financial situation following the death of his eldest brother, and his short-lived marriage to Marcelle Charlotte Guyot de la Hardrouyère, which ended that July, his career was about to take off. He was the first Chinese artist presented at the Salon des Tuileries in 1930 and the Salon des Indépendants in 1931. In the same year, at the age of 30, Sanyu featured at the Annuaire – Tous les Arts, published by Marcel Schmidt. A year later, he was the only Chinese artist listed in the Dictionnaire biographique des artistes contemporains 1910-1930, published by Joseph Édouard. Over the next few years (between 1931 and 1934), he organised 5 solo exhibitions in Paris and the Netherlands that received favourable reviews from art critics and journalists. It is fair to say that Sanyu was the most famous Chinese artist in France and Europe during the 1930s.

Retrospectively, we know that the 1920s and 1930s were the happiest decades of Sanyu’s life. This was also the most creative and productive period of his career when he produced over 2,000 drawings and watercolours, and started experimenting with oil paintings (1929), prints (1930), mirror paintings (1931) and sculptures (during WWII) using his newly acquired skills and knowledge of Western techniques and materials. He also found time to invent his signature sport – Ping-Tennis. The 1940s was a relatively quiet decade for him and little is known about his life during this time except for his brief stay in New York (1948-1951). He went there in the vain hope of promoting Ping-Tennis and left 29 oil paintings with the photographer Robert Frank who shared a studio with him in the city. The failure of the American trip redirected his focus and energy back to painting during the 1950s. Among the last corpus of work that he produced during this period, until his death in 1966, are the 42 paintings he sent to Taipei in 1964. This was in preparation for an exhibition at the National Museum of History, but the exhibition was never realised until 2017, when all the paintings were restored and shown to the public for the first time at Paris Nostalgia – the National Museum of History’s Sanyu Collection, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Sanyu’s death.

The three decades of Sanyu’s artistic career, from the 1920s to 1940s, particularly his first encounter with Paris and Modern Art, are the focus of a more recent exhibition at Tina Keng Gallery, Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms – Through the Eyes of a Dandy (Taipei, 24 March to 29 April 2018). While the Paris Nostalgia exhibition focused on the late phase of Sanyu’s life, the Hidden Blossoms exhibition aims to fill in the void of the former show, and shed some light on the early stage of Sanyu’s life and work. This is done through its portrayal of a young dandy who was in constant pursuit of his artistic muse, while also keeping an intellectual distance from his surroundings. The show also attempts to create a bridge between the art of Sanyu and today’s young artists and curators by entrusting the curatorial work to the gallery’s curator, HSU Fong-Ray (許峰瑞), who is also in his early 30s.

The show starts with a reconstruction of a scene at the Grande Chaumière in the 1920s where Sanyu indulged in his nude drawings and watercolours. Works are casually placed on wall shelves and the concrete floor gives way to dark oak wood flooring that is reminiscent of 1920s Paris. The ink drawings and watercolours of the nudes are the first series of Modernist works that distinguished Sanyu from his fellow Chinese artists. While the others were diligently studying anatomy and Western techniques, Sanyu was consciously searching for a unique personal style in the exotic and delirious world that Paris offered in the roaring twenties.

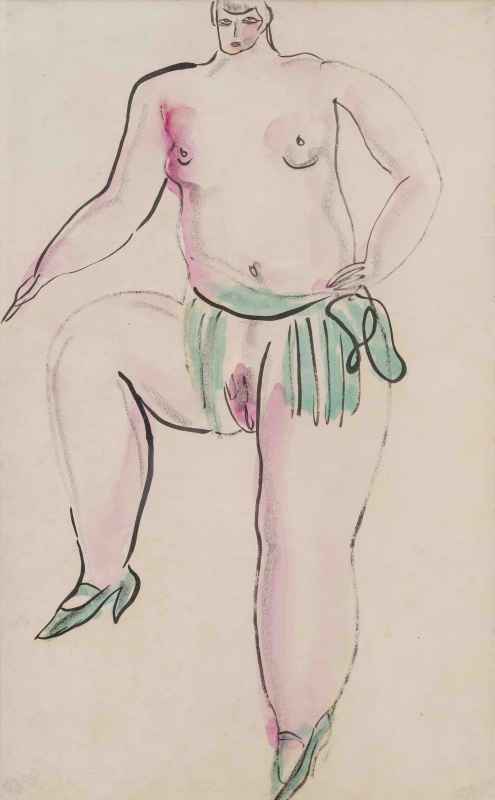

Sanyu’s drawings are characteristically minimalist and precise. His lines are expressive and never retouched. He employs smooth lines with varying degrees of density to outline the contour of the nude body, while shading is used to give the body volume and shadow. The nude women in Sanyu’s drawings are either standing, seated or reclining. Framed from head to toe in an empty space without perspective, their massive bodies take up at least three-quarters of the drawing’s surface, eliminating any indication of time and space.

Untitled (1920s), for example, embodies all the characteristics of Sanyu’s nudes: a single eye, a nose reduced to a point, and lips that are always closed. Her hands and feet have metamorphosed through an autonomous drawing process into animal paws and claws; the lower part of her body is deformed and exaggerated to become the “cosmic thighs”, while her head is greatly reduced to create an illusion of perspective, as if we were looking at the giant nude body from below her knees. With folded arms and legs, she concentrates on herself, refusing to communication in any way or be interrupted. The two principal lines run smoothly along the sides of her body – one from her right shoulder to her right knee, the other from her left armpit all the way to her left big toe, illustrating the spirit of Chinese calligraphy – “writing in one breathe” (一氣呵成). These lines are executed with great economy and precision, without any retouching, and call to mind Sanyu’s solid training in Chinese calligraphy and the art of Henri Matisse, in particular La danse (1909-1910) and La musique (1910). Thus, Zhang Daqian called Sanyu the “Chinese Matisse”.

The distortion of the female body also echoes the visual experimentation of the modernists, such as The Buveur (1925) by Vicente do Rego Monteiro (1899-1970), the Brazilian painter who lived in Paris from 1921, or André Kertesz (1894-1985), the Hungarian photographer and painter who lived in Paris from 1925 and started the series, Distortion, in 1933 with a magic mirror attached to the lens. We can say that in the 1920s, Sanyu joyously participated in the creation of new images and did this with a new sensibility that was unique to l’École de Paris.

Vicente do Rego Monteiro, The Buveur, 1925.

André Kertész, Distortion #34, from Distortion series, 1933.

The combination of Chinese ink and Western watercolour was a new creation of Sanyu. In À Garby (1929), a portrait in Sanyu’s signature composition, he replaced charcoal shading with watercolour shading in three primary colours: green, red and brown. These colours are more ornamental than functional in the sense that they are done spontaneously, regardless of anatomic rules, and they capture the sensuality of the sitter rather than highlight the volume of the mass. Since perspective didn’t interest Sanyu, his depiction of volume became less prominent in the decades to come, while the tendency to flatten the subject to extreme simplification became more evident. Despite his minimalist impulses, Sanyu managed to capture the fashion of Paris. In a series of portraits of his fellow artists in the Grande Chaumière or in the cafés, Sanyu carefully detailed the makeup, the dresses, the jewellery, the hats, the accessories, the boots, and the black silk stockings of these beautiful Parisian women.

Sanyu, Resting Girl, 1920s. Watercolour on paper.

Sanyu, Seated Lady on an Armchair, 1920s. Watercolour on paper.

Sanyu, Seated Blue Haired Lady, 1929. Watercolour on paper.

The nude is the most evolved and abiding subject in Sanyu’s work. As a result of his desire to integrate into the Paris modernist art scene, and with the encouragement of his patron Henri-Pierre Roché (1879-1959) – a great art dealer and patron of many Modernist artists – Sanyu started experimenting with oil paintings in 1929, first with nudes, then animals, still life, landscapes, etc. The first oil paintings executed in this period were predominantly pink in colour, which for Sanyu denoted the gentleness of femininity. Hence, this period is also known as the “pink period”. Two Standing Nudes (1930s) belong to this period. The colour scheme is still reduced to three: pink, white, grey. The nudes are placed at the eye level of spectators, and so the exaggeration shifts from distortion to the roundness and voluptuousness of the bodies. With this new physical feature, the hair and the physiognomy of the two nudes resemble the courtesans of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) rather than the blonde women of the previous decade. Sanyu’s nudes get slimmer as time passes, and their skin changes from pink to ochre, while retaining its transparency. Thus, this period is known as the “ochre period” (from the 1950s onwards). Bather (1950s-1965) and Nude (1950s-1965) are the “ochre period” nudes.

Sanyu, Two Standing Nudes, 1930s. Oil on canvas.

Sanyu, Bather, 1950s-1965. Oil on masonite.

One important aspect of Sanyu’s work is its pervading undertone of eroticism. While the other Chinese artists were still uncomfortable in front of a nude model, Sanyu was intoxicated with the voluptuous bodies of occidental women. His early nudes in the 1920s, such as Nude with Green Shoes (1929), Seated Lady on an Armchair (1920s), were born from a combination of voyeurism, imagination and eroticism. It was certainly a personal choice for Sanyu to eroticise his models, but the freedom granted to him by Paris, the popularisation of Sigmund Freud’s theory of Eros and the subconscious in the 1920s, and the erotic art of Auguste Rodin and Gustav Klimt could all be sources of inspiration for Sanyu.

Sanyu, Nude with Green Shoes, 1929. Ink, charcoal, and watercolour on parer.

Sanyu, Seated Lady on an Armchair, 1920s. Watercolour on paper.

If the nudes in the previous years were gracious and hypnotic, the women Sanyu painted in the later stage of his life exhibited an erotic charm without pretension. Despite the simplification of female genitals into an exclamation mark or a circle, the ochre nudes painted in the 1950s-1960s, such as Nude (1950s-1965), are evidence of Sanyu’s hedonism as a dandy who united an intense implication with a distant effect in his art. This ambivalent attitude uses subterfuge to transform women into animals: hands become claws, feet are paws and faces are ambiguous. Their sex is exposed to nature; they stretch out their body, or pull their legs close to their chests like animals. For Sanyu, women were mysterious animals that proved intensely attractive and yet belonged to a different species from his own.

Like his nudes, Sanyu’s still life is highly exotic and surreal. The choice of flowers – mainly lotuses, chrysanthemums, peonies, plums and bamboos – strongly recall the tradition of Chinese literati painting. Yet, Sanyu painted them on different surfaces, including canvas, mirror, wood, masonite, paper, and even cardboard. He would scrape the paints, dry or wet, to create fine lines that contoured the objects. Such a technique worked perfectly for him since the barely perceptible lines translated the delicacy of the flowers. Along with his reduced palette and soft colours, such technique highlighted the lightness of flower painting that is found in the Chinese tradition. Sanyu loved to mix different species and colours of flowers together in the same stem; and the presence of animals animated the festive mood, including butterflies flying around flowers, birds resting on a single stem, a couple of frogs talking to each other, etc. In Cat and Birds (1950s), which is included in the current show, Sanyu painted a nest on a plant of stems without leaves. But the nest is not empty: a mother bird is feeding her babies. A cat, ridiculously small, is placed under the stem and is stretching its neck towards the nest with unfulfilled desire. Is this an image of the artist himself? Is he mocking himself with the absurdity of the little cat?

Sanyu, Still Life of Flowering and Fruit Plant with a Green Ground, 1950s-1965. Oil on masonite.

Sanyu, Cat and Birds, 1950s. Oil on masonite.

The choice of animals in Sanyu’s paintings is equally exotic: pets from his native country or exotic animals from a zoo, such as zebras, leopards, tiger, giraffes deer, elephants, hawks, eagles or snakes. They come alone, in a couple or in a group. In the earlier works, we see cats and Pekinese dogs in a domestic setting – sitting on a chair, playing on the floor, or drinking milk. The gesture of an animal is more important to Sanyu than its volume or placement in the space. In other words, he is not interested in the animalistic aspects of his subjects, but their hidden sentiments that could be similar to human beings. Thus, we often encounter unexpected expression or attitudes in Sanyu’s animal paintings – a leopard sitting in a vast landscape waiting for an unknown something; another lying down totally absorbed in its own thoughts; a loving animal couple intimately embracing each other, or looking at each other, or sharing food. If sex has tended to be irrelevant in the tradition of animal painting, this is certainly not the case with Sanyu, particularly during the “pink period”, where his animals exhale a sentimental charm similar to his nudes. They are the embodiment of a seductive woman who is attractive yet distant, sensual yet enigmatic.

In the 1950s, Sanyu placed exotics animals in a vast isolated landscape where they become the hosts. The predominant sentiment or theme in these paintings was the solitude that the artist felt in his old age. He created two paintings that represent a lonely elephant walking in an immense desert, the later (which is in the show at the gallery and considered to be one of his latest works, as it was done in the 1960s) has a layer of black and grey paint that covers the lower part of the desert in yellow. This adds a heavy sobriety to the aging elephant, who is painted in black, in contrast to the galloping baby elephant in white of the previous decade.

In the 1960s, Sanyu declared that “after a life devoted to painting, I finally know how to paint”. In fact, not only did he know how to paint, but he participated throughout his life in both the creation of a new aesthetics and in the research of modernity in the School of Paris, just like any other foreign artists living and working in Paris at that time. His intuition to stay in Paris during his younger days – it was the only place where he could live his life as a Modernist painter – while most of his compatriots returned to China after their studies, reinforced his determination to be part of the Modernist movement. However, his nonchalance, scepticism towards the art market, and idiosyncrasy gradually eroded his potential commercial success in the early 1930s. These precious opportunities slipped through his fingers and never arrived again in his lifetime. Nevertheless, Sanyu continued his artistic struggle in poverty until his death in Paris in 1966. An artist who was little known during his lifetime, Sanyu then fell into oblivion.

A lost artist was rediscovered. It was only in the closing years of the 20th century that we began to understand the modernity that is found in Sanyu’s art. Thanks to the National Museum of History in Taipei, three exhibitions were organised in 1984, 1995 and 2001, followed by a retrospective in the Musée Guimet in 2004. So far, around fifteen exhibitions dedicated to the work of Sanyu have been organised. Exhibition catalogues and catalogue raisonnés have also been published in the last two decades, as well as a detailed biography by Rita Wong, the former specialist of Sotheby’s Taipei. The market also started in the early 1990s, thanks to the efforts of Taiwanese galleries, such as the Lin & Keng Gallery (1992-2009) and Dimension Art Centre in the early 1990s, and then the Tina Keng Gallery(2009-), rooted from Lin & Keng Gallery to present.

Tina Keng, who has organised seven exhibitions of Sanyu’s work and edited several publications, is instrumental in re-establishing the artist’s historical significance, both in the market and in art history. Keng first came into contact with Sanyu’s work in 1988 and since then has been devoting her time and energy to the artist and his work. She points out that despite several auction breakthroughs, the market for Sanyu has not quite reached the ceiling, as there has been an increase in the demand for Sanyu’s work from Mainland China. However, it is now most important to bridge Sanyu’s artistic vision to today’s young generation. He is a pioneer in the eyes of Tina Keng, and it took 50 years for the public to truly understand and appreciate his avant-garde spirit and artistic experiments.

Keng urges the market to regulate and operate with integrity, however, as a mark of respect to Sanyu. She warns the public about the problem of fraudulent works. After over 30 years of carrying out research into Sanyu and dealing with his works, Keng has developed a set of criteria that will help the public to judge the authenticity of a Sanyu artwork. In an interview given to CANS Asia Art News in 2009, Keng laid out her observations. Firstly, according to Keng, Sanyu has a solid foundation on Chinese calligraphy and epigraphy, thus his treatments of spatial relationship, lines and brushworks are never messy. Secondly, as a gracious and minimalist person, his works carry the same clarity and rigorousness in their texture and composition. Thirdly, Sanyu’s aloof and indifferent disposition is reflected in his work, so none of his work feels vulgar. Keng points out that most frauds are from the still life series. As well as the three tips mentioned above, it is worth noting that Sanyu’s flower paintings exhibit strength and life in an organic way, his plants look upward and give the impression of growing and being full of energy. They are never dull or still. “One has to see the real works, and many of them, to be able to tell if a painting bears his temperament, which is unique to Sanyu,” said Keng. While cultivating a new generation of artists, curators and collectors who appreciate the art of Sanyu, Keng hopes that scholars and art historians will take over the Sanyu craze from the market and establish the artist’s academic value and historical contribution.

Sanyu’s art is deeply embedded in the originality of the artist himself and his own sensibility towards the Modernist tendencies of his time. When we look at his work, we can hardly believe that they were done by a Chinese-born artist in the Qing Dynasty. Sanyu is a Modernist Chinese painter and he has become a Modernist painter of China, but he belongs to the 20th century avant-garde group of international artists. Such a positioning of Sanyu’s art explains the apprehension that his contemporaries felt in front of his work. Today, with hindsight, we can re-acknowledge both his originality and his modernity.

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms – Through the Eyes of a Dandy

24 March – 29 April 2018

Tina Keng Gallery, Taipei