CHAPTER 1. Meeting Herman Daled

When we sat down in the living room of the famous Maison Wolfers where Mr. Herman Daled lives since 1977, I was nervous, Herman was confused. Notorious for turning down interview request, I knew my luck to be sitting there and my real challenge to make him talk. He looked as anxious as I was, a little impatient. “I don’t know why you wanted to interview me,” he said, “as you can see, I am not an artist”. So we laughed, and started our time travel back to 1966.

A man of intellectual pursuit and innate sensibility, he seeks knowledge in life and sees beauty in truth. He lets go of his emotions and he allows himself moments of perplex. A man of modesty and exigency, he gives himself a footnote role while living his life as one of the most ardent supporters of conceptual art. “I don’t deserve any credit except that I was a bit fool!” He laughed. “But it’s true! Because I don’t know what took hold of me… now that I have to live through all these again…” A long, long pause… I dared not to disturb him.

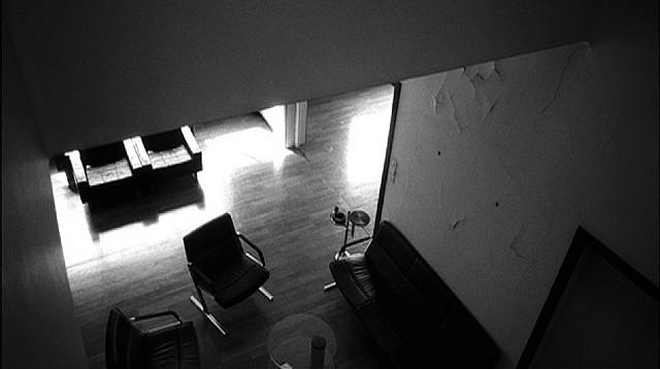

CHAPTER 2. Three Chairs and A Peeling Wall

The walls are peeling, time elapses. The house is bare, in semi-ruin. Empty chairs and empty walls, it’s a rule in the house – not to crucify art on the walls.

Herman finally stood up to slide open the doors on both sides of the living room. Huge volumes of the 1930 Henry van de Velde building revealed. Again, empty chairs and empty walls. Three white chairs are posed in front of the window, each with a tin of paint and a brush sit neatly on it, rather conceptually. “This is not a work of art”, declared Herman. I know. “How did you know?” He was intrigued. Hidden behind the serious look of a radiologist is a very special sense of humor. He has the rebellious genes of 1968 in him. His children offered him chairs and paints for Christmas, and it’s the father’s task to paint the chairs blue, red and green. So here they are neatly arranged, intact. A joke for his guests who expected him to perform a collector’s role?! I tried to image a 36 year-old young man cashing half of a car for a piece of A4 paper signed by a certain Weiner.

CHAPTER 3. The Hotel and The Collection

Taking the path through the garden to the garage, I looked up again at the 3-storey hôtel particulier. It turns its side to the road in an “L” shape, cleverly creating a secret garden at the centre. Discretion is the catchword.

When I met Herman again in Venice, he told me that the collection finds its ultimate home in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. A collection that rightly compensates MoMA’s lack of the root of conceptual art.

Selina Ting,

Paris, 6 October 2011

Being a Collector and Becoming a Collector

Selina Ting : You have been invited at several occasions to participate in conferences and seminars regarding the role and position of the art collector. I have read a paper written by you in 2001 on the vices and virtues of a collector. Are you always interested in the subject?

Herman Daled: A subject matter that I am contemplating nowadays and that I am personally concerned with is the nature of a collection and the status of a collector. When talking about collections, we have to distinguish the differences between building [faire une collection] a collection and owing a collection [avoir une collection]. While when we talk about collectors, we have to distinguish being a collector and becoming a collector. So, here we have four keywords: to build, to own, to be and to become. In the case of collectors, of which I am not one (and it annoys me all the time), we have: to build and to be. Someone who is a collector and wants to build a collection has an idea from the very beginning. Once he sets off his adventure, he has no other ambition than to make the collection as complete, complex and exemplary as possible. Is this a vice or a virtue? I don’t know. I am not an expert or art historian. Let me remind you that I am a doctor.

For example, the philatelists keep their stamps in albums with pre-printed blank cases. When a collection of a certain edition is complete, all the cases will be filled up. This is evil, Machiavellian, because he who wants to make a collection would be sick as far as a blank case is left behind! And he has to fill it up at any expense! The same mentality applies to certain people who want to build an art collection. I have seen several cases around me… people talk about guidelines, a sort of framework when one builds a collection. Such frame can be well-defined, or with vague boundaries and it can evolve with time, but the concerned person is a collector and hewants to build a collection.

Now, let’s look at the other case, i.e., he who becomes a collector and owns a collection. We can take the image of a jazz lover as illustration. A jazz lover starts buying discs in order to listen to the music which is the thing that interests him. He is passionate about the music. He keeps buying more and more discs but his aim is always the same — his interest in music. After a certain time, he would have a pile of discs. If these discs have a high quality, a historical significance, an economic interest or an archival value, then he owns a collection, but he has never built a collection. I put myself in the second category. I have never wanted to build a collection and I am not a collector, but I have a collection and therefore I became a collector. Is it clear?

ST: Yes, it’s clear!

HD: I think these differences are very important.

ST: In the second case, one evolves at the same time as what is happening, while in the first case, it implies an obstinacy in obtaining certain precise pieces, hence a constant competition to be the first person to complete the blank cases.

HD: Today, if someone wants to build a collection of conceptual art, he would try to have the works of all the great artists of that period, Lawrence Weiner, Carl Andre, So Le Witt, etc.

ST: But time flies, that period belongs to the past. So, according to you, it’s no longer possible to build a collection of such kind today?

To “collecter” is to gather

— Herman Daled

what one comes across during these wanderings.

That’s why I insist on the fact that

what I have done is not a collection

but putting together

what I came across during the years.

HD: There is another aspect on which I would like to insist, i.e. the difference between the French words “collectionner” [to collect with a specific intention] and “collecter” [to gather]. As I explained before, “collectionner” comes with the idea of building a collection, of searching for the precise pieces and of keeping a harmonious group of objects, whereas “collecter” means to gather together objects while taking a walk. In church, one collects donations by walking amongst the assembly with a small container. In the countryside, in the past, one used to collect milk-churns. Hence, the word “collecter” implies a wandering. When you go for a walk, you collect a bunch of flowers. Naturally, this bunch of flowers gives trace of the places where you have been. The flowers you gathered from a walk in the wood would be different from those you gathered from a walk along the river. Therefore, “collecter” is to gather what one comes across during these wanderings. That’s why I insist on the fact that what I have done is not a collection but putting together what I came across during the years.

ST: In the 19th Century literature, we have the image of the flâneur who, guided by sheer chance and curiosity, collects the impressions offered by a modern metropolis. Is there any similarity between flâner and collecter?

HD: It’s more or less the same idea.

The Setting Off

ST: How did you set off in such a long wander?

HD: I took interest in visual art because in my family, three generations have been interested in visual art. At home, we didn’t have music or literature but paintings everywhere. Thanks to my grandfather, I grew up surrounded by primitive Flemish art. Then my father, who wanted to be different from his father, focused mainly on Flemish Expressionist painting. Then my turn came and I did something else.

ST: So, contemporary art…

HD: I was very much influenced by two persons in my life. The first one is the cytologist Professor Albert Claude, who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine, and the second person is a poet, Marcel Broodthaers…

ST: A poet more than an artist?

HD: Yes! He is poet who makes art, but after all he is a poet, a magical poet! [Laughs] Something particularly determinant in my life is the influence of Professor Claude. In 1969, the year of the historical Moon-Landing that caused much public sensation, Professor Claude, who received his Nobel Prize five years later (in 1974), did the opposite trajectory. Departing from the visual world that surrounds us, he went all the way to the surface of a cell. Compared to the scale, it was already an enormous journey. Then, from the surface of the cell, he entered into the cell. Like the spacemen who brought back to the earth samples of soil from the moon, Professor Claude was the first one to collect samples of what is inside a cell. The journeys from the visual world to the moon and from the visual world to the cell are of the same distance: one towards the infinitely grand and the other towards the infinitesimal. In addition to his talents in science, Professor Claude lived his life with a passion for music. He immersed himself in contemporary music (Iannis Xenakis, Pierre Boulez, etc.) It was him who encouraged me to develop my interests in contemporary art and to quit the routines of my family culture. From that moment on, his idea motivated me to pay attention to what was going on at present. It was like this that one day in 1966, I stepped into a gallery in Brussels where I discovered the work of an artist then totally unknown to me and I immediately bought one of the work in the exhibition. That was how I made acquaintance with Marcel Broodthaers. Like every exhibition, there was a dinner following the opening and we were three: the gallery owner, the artist and me. It was like this at the time, two or three guests; five guests were already a lot. After the dinner, we became very close friends. I had a very close relationship with Marcel and I had a profound interest in his work.

ST: How old were you at that time?

HD: I was born in 1930 and all these artists were born around 1938. I bought the first piece of work from Daniel Buren in 1969, and Niele Toroni as well. They were both 31 years old. I don’t know if you have heard of the gag…

ST: The contract?

HD: The contract. In 1970, Buren said that I wasn’t a serious person and that I should concentrate more on what I was doing. So we made a deal that during a whole year, I should not buy any artwork except one painting per month from him. That’s why I have twelve big paintings from Buren.

ST: Why such an idea appeared interesting for you?

HD: There is another point that I should explain to you. In addition to what we have discussed on the concept of collecting, we can also distinguish certain differences among objects in general. They can be big or small, heavy or light, etc. But there exists a difference between what we called “objects of knowledge” and “objects of pleasure”. Always under the impulsion of Professor Claude, I have been first of all looking for objects of knowledge and I am very suspicious towards objects of pleasure. For example, as soon as an artwork appeared beautiful to me, I knew that I should not be interested in it. And this is very true. Because when you are seized by a sense of beauty, you always have a subconscious reference to which you identify what is in front of your eyes. Let me explain. When I say “a handsome man”, I have the impression that you see one of a certain type but in reality you see another one.

ST : David of Michel-Ange or David Beckham ?

HD: [Laughs] There is always something subconscious. I think that a “beautiful old man” refers to an image of an old guy with all the traits of what an old man should have. I was a doctor in radiology, I was a professor as well. In the late mornings, I gave seminars to my students and I told them, “we are going to examine a beautiful cancer”. What does it mean? It means that the images I was about to show them carried all the characteristics of what they had learnt from their text books. Because they read the descriptions of a stomach cancer, for example, and when I showed them the images that corresponded to what they learnt, they would recognize the cancer and say that it’s a beautiful case. There is a notion of truth in beauty, and truth presupposes a former utterance.

There is a notion of truth in beauty, and truth presupposes a former utterance.

— Herman Daled

Now, let’s come back to my interest in conceptual art movement. I believe that they are “objects of knowledge” because they reveal to us new aspects that have nothing to do with the techniques, the know-how, or the subjectivity of the artists. It was very cold, aesthetically very bare. I am interested in this because, for me, they are objects of knowledge and not objects of pleasure. I found a total satisfaction in all these documents or artworks that are for me objects of knowledge.

I don’t ask artists to make me beautiful things. I am not interested in that. But I want to see interesting things in their work. I think what’s so unique about a creator is that he creates new values that later on become aesthetic values in their own right. I am not an art historian, I repeat. But I think that it’s a common point to all the artists who have been true innovators to have been rejected at the beginning, be they the impressionists, the cubists, etc… because they disrupted people, because they brought new ideas.

ST: Because they are ahead of their time?

HD: The artists have a vision of the future. They have their own unique vision. I don’t like the work “progress”, I don’t think there is “progress” in art but there is evolution. And the artists push art towards another limit. After conceptual art, there is photography, installation, etc.

ST: Often it’s with time that we understand better what happened in the past.

HD: Yes, we just need to wait for 10 years, 20 years, 30 years, with the effort of the media, education and museum visits, then the public would assimilate these images, and then, what happen to these images is that… they become beautiful!

Objects of knowledge

ST: Is it because you search for objects of knowledge that you are against the idea of showing the work on the wall?

HD: Objects of knowledge should not be stuck on (the wall. I am really hostile towards the idea of hanging artworks on the wall. It’s a rule in my life. I don’t want artworks in my house, except some little pieces that lie around. Because it’s terrible, once you put a piece of artwork on the wall, at the end of two weeks, you don’t see it anymore. It’s over! It happens to me that, when I have friends visiting and when I feel that the works will not be rejected by sarcasms or misunderstandings, then I take a few pieces out, put them by the window, on the floor or on the couch. We look at the works and the next day, I put them away. All kinds of pleasure are ephemeral: reading, theatre, music, museum visit, holidays, gastronomy, etc. I strongly believe in this. On the contrary, the bourgeois have now decided to put the artworks on the wall where they are displayed continuously. They then start to merge with the décor, the furniture, etc. they are dead! I think that for an artwork to have a real impact, it should be in a condition in which it can be closely studied. A book, we read it only once, perhaps twice if it’s really extraordinary. Why should a work of art be always visible on the wall?

ST: But isn’t it true that every time we look at a work with fresh eyes, we may have a different interpretation and understanding?

HD: That can change with time. Time elapses, perspective shifts, perception changes as well. We don’t look at a work of 1966 in the same way as we did in that epoch. Our perceptions might be influenced by what the artists did afterwards. I come back to the period from 1966 to 1978 when my ex-wife Nicole and I made choices of artworks. It was really an emergent and creative period in the career of the conceptual artists. I think that all the artists pass through a period of high creativity before they are greeted with success, then they enter a period of high productivity, which means they have assistants, and they start making big-scale works, and after the big-scale works, they make monumental works. I am not fan of gigantism.

ST: The first piece of artwork that you bought is Marcel Broodthaers Maria’s dress in 1968?

HD: Yes.

ST: You still have it?

HD: Yes.

ST: Do you look at it, sometimes?

HD: Yes, I look at it with a lot of emotions, sometimes! I am very happy to discover it, sometimes!

ST: [Laughs] Why did you buy this piece? Under what kind of impulsion did you buy it?

HD: I am more interested in the reflections on what a collector is than what I have done. I think what’s important is that: What is it that motivates a collector? Sometimes I say that a collector may be nothing more than a pair of eyes that see what the others try to think later. By this I mean that a collector is a man of action. He does not talk, he is not an art critic, but he acts, he poses himself as the possessor of artwork. When we recognize later on that the work has a certain value, there are art historians, scholars, elites, etc., who start writing thesis and theories to explain things that the collector won’t even able to understand!

ST: [Laughs] Genius!

HD: [Laughs] But that’s true! I have read lots of things written about Maria’s Dress, about the vacuity of the eggs, of the dress… I have never thought of all these. So to reply to your question, why did I buy this dress? Why was I so strongly impressed by it? I would like to go back to the political context of that period: we were briefly before May 68 and the artists were hostile towards museums and institutions. This attitude was fundamentally on the same stance as conceptual art. When I saw Maria’s Dress at the opening, I really had the impression of confronting the immateriality and the ephemeral par excellence. It’s a piece that Marcel had conceived on the same day. His wife Maria received the dress from her sister in the Netherlands as a gift that morning when Marcel was requested by his gallery to make a work for the gallery entrance. So when the parcel arrived, he went to buy a huge framed canvas, he nailed a stud onto it; he took the dress, put it on a hanger and suspended it on the canvas. Then he took a paper bag and put the eggs onto it. When I saw the work, I thought it was going to be destroyed in a month, because I had no idea what the materials would become, if the moths would eat it or whatever. But it was exactly this [uncertainty] that motivated me, because for me, it registered the context [of the time]. And we see the same absurdity and provocations in the acquisition of 12 identical paintings from Buren one after another, and again in the case of Niele Toroni. I bought a 12-meter rolled painting from Toroni in 1969. Three years later, he was still doing the same brush prints, so I told him that it wasn’t worth the trouble to tire him with another painting, I would just buy the same painting again. But since three years have passed, he raised the price. All these gestures have an impact. I think that’s why today we find an interest in them.

ST: Do you think that if you didn’t participate in these projects, another collector would have been there ready to replace you for the realization of these projects?

HD: Yes, I wasn’t the only one. There were collectors in Germany and the Netherlands who supported the conceptual artists. In any case, what happened to me was totally by chance, and I have seized the chance. I am not blessed with an exceptional perspicacity. What I have is enthusiasm and an interest in the things. It happened that the American conceptual artists had a bigger audience in Europe than in the States at that time. Because in America, they were more materialist and it was still the heyday of abstract expressionism with Clement Greenberg, etc. Conceptual art had practically no audience in America at that time. On the contrary, in Europe, there were many galleries and museums opening their doors for these artists. Don’t forget that in 1969 there were three major exhibitions: When Attitudes Become Form in Berne, Op Losse Schroeven in Amsterdam and Conception in Leverkusen. Then in 1974 there was Harald Szeemann’s Documenta 5 which became the consecration of conceptual art. Therefore, it was truly a movement even though they were not numerous. They were perhaps 15 in total. And the chance was that at that time, they were all invited to Europe. We sent them a flight ticket and they made their work on site. Also, it so happened that at that time, the low-costs airports were in Brussels and in Luxembourg, which means they all stopped by Brussels. And they didn’t know anybody here except Marcel Broodthaers. So in the evenings, Marcel brought them to my house. He told his artists friends, “No problem, I know where we should go tonight. We can drink there, eat there, smoke there and what’s more, they buy.” And this was true!! Since the majority of the work is on paper, it was very easy to travel with. The artists came to the house with their work, put them here and left with a check or cash. That was how things were done.

ST: Is it possible to understand the value of a work of conceptual art in monetary terms?

HD: I give you an example. A work of Lawrence Weiner, which is basically a piece of blank A4 paper with two little arrows, on the paper, it’s written “middle of road” or “be right of the centre” or “as if it were”, etc., and this cost half of a car! For Lawrence, it’s a very intelligent and pertinent strategy because by doing so, he meant that his work was equivalent to any conventional artwork, be it a painting, a drawing, a bronze, etc. Therefore, his work should be sold at the same price as any other artwork. Again, for this strategy to work, he needed to find… [Laughs] buyers who were ready to say “ok, I agree with you”. I wasn’t the only one but there weren’t many. And we bought these pieces as works of art. It’s still the same today. All conceptual art was just like this… A piece of work of Richard Long costs a car!!

What is happening right now is that

— Herman Daled

there are no longer real waves

but artificial ones created by the media,

and they change every year.

For me, the art world is now becoming a Jacuzzi!

ST: Retrospectively, how do you consider your role in the art world in the 1960s and 70s?

HD: You know, I don’t have any credit to claim. I am totally convinced of this. I was simply the right man in the right place at the right moment! It was nothing more, nothing less than a simple coincidence! I don’t deserve any credit except that I was a bit fool! [Laughs] But it’s true. I think I was a bit fool, because I don’t know what took hold of me… [Pause] now that I have to live through all these again… [Pause] But it was fool, it was fool, because… [Long Pause] At last, I don’t know why. It’s very strange, because I am not a wealthy person at all. All I had was the salary I earned from my work.

ST: The years around 1968 were a period when the young generation was hunger for new ideas and strived to break away from all conventions. It was an epoch that was deeply marked by revolutionary ideas.

HD: Yes, I think you are right, because what I was doing at that time, I could not continue in the later years and even less nowadays. To build a so called “avant-garde” collection is an offered occasion, a chance. It can’t be improvised. You need to have a group of artists in front you, and by this, I strongly distinguish it from that kind of artistic movements that are taking place nowadays. An artistic movement means a mutual-support group of artists who share the same preoccupations but express them through different aspects. When considered in entirety, their works are capable of arousing your interest. I always say that it’s just like a surfer on the waves. The surfer is the collector, the surfboard is the logistic tool that he needs, which means a bit of money and time, but the essential element is the wave. From time to time, there are some waves in the art world that change our perception of art. What is happening right now is that there are no longer real waves but artificial ones created by the media, and they change every year. For me, the art world is now becoming a Jacuzzi! [Laughs]

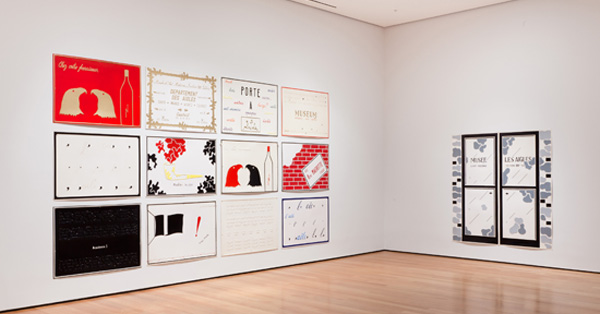

Munich 2010

ST: You showed your collection in Haus der Kunst in Munich last year (October 2010). It must be a very rare thing that you would do, isn’t it?

HD: It was the idea of Chris Dercon, the then director of Haus der Kunst and currently Director of Tate Modern. I have known him for a long time and it was him who insisted that I should present the collection in Munich. So I said to Chris “OK, but I have a problem, I don’t know what I have in the collection”. I have accumulated the pieces, but as you see, I have nothing in my house. He replied, “No problem. I will send a team and we will take care of the inventory”. Two people from the museum came to Brussels and spent two months here to work out the inventory of the whole collection. When it was done, they decided to make a “cut” and said that they would like to present in Munich the acquisitions – it’s an important word here – made between 1966 and 1978.

There, what represents the exhibition in Munich… obviously it’s called a collection, but for me it’s a sample, a witness, I use the word “leftovers”, the residues. But Munich didn’t like the word and didn’t choose it because it’s not chic. [Laughs] Anyway, I call the collection the “leftovers” of my action, of what I could do while wandering and collecting during this period. And today they became the witness of what happened at that time among a group of artists who have earned a historical importance that is recognized by the whole world today.

ST: How did you feel when you saw the collection hung on the walls and shown to the public?

HD: It was very nice. I didn’t interfere in the organization of the exhibition and I was very happy of the hanging and the overall work of the staff of the museum. One of the precious things about the Munich exhibition is that, by chance, Nicole has conserved all the archives of that period. The importance of printed-matters was one of the remarkable things at that epoch. We have to resituate the Conceptual Art Movement in the political and economic context of that time. In the States, it was the Vietnam War and the student protest in Berkeley; in Europe, it was the May 1968, etc., There were very strong movements that the conceptual artists were engaged with, and effectively, they tried to boycott or bypass the cultural institutions. For example, they made some printed materials for their exhibitions which sometimes were more important than the exhibitions themselves. That is why the archives were important. It was really interesting to see them in Munich. You have artworks hanging on the walls, and in front of the works, you have the vitrines. But the demarcation line between the artworks and the archives was very blur. You couldn’t really tell whether the hanging ended there or every single item on show was a piece of art. This was very characteristic of that period. But it belongs to the past, it’s history now, it’s dead. At last, this is what history is.

ST: Thank you very much!